In China, Daoist temples atop mountains are so numerous that there must be something about these high places that answers a longing for cliff edges and being above the clouds. A simplistic analysis of this, one using that most ignoble of human faculties; the so-called common sense, would say that this was driven by a wish to be closer to heaven. But, much like the western view of Hinduism, this is more than a mere bowdlerisation; it is complete bollocks.

To be sure, I climbed one.

“We have a choice,” said Cesca, sitting comfortably in our guest room in Li Jiang.

“OK” I said putting my book down.

“We are heading to Chengdu and the Pandas, then Xian and the (terracotta) Warriors. But, after that we can go either to Wudang or Song.”

I thought about this. Song Mountain is probably the most famous mountain in China. The stories of that holy place and the dramatic history of the men who lived there permeate western culture like no other legend China offers. You see, Song is where the Shaolin temple resides. I also knew it was only a pale shadow of its former self.

The “temple” is more a tourist trap now for it has been famously burned down and rebuilt more than once, more than twice. The last time, during the Communist revolution, resulted in the deaths of most of the monks and it was only the tourist’s fascination with this temple that led to it being brought back to life.

Wudang, while not as famous, also has some exposure in the West. It is often featured in the same classic movies as Shaolin, but usually cast in the role of the antagonist. Recently it has appeared in three Hollywood movies that spring to mind: Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon recounts the adventures of a swordsman from Wudang (although the temple seen in the movie is not the real one),

Li Mu Bai: No growth without assistance. No action without reaction. No desire without restraint. Now give yourself up and find yourself again.

The Bride’s master from Kill Bill 2, Pai Mei, is based on Bak Mei of Wudang,

Pai Mei: It’s the wood that should fear your hand, not the other way around. No wonder you can’t do it, you acquiesce to defeat before you even begin.

and the (new) Karate kid bizarrely features the young hero learning the snake forms from observation of a master high up in the mountain.

Mr. Han: Chi. Internal energy. The essence of life. It moves inside of us. It flows through our bodies. Give us power from within.

I also thought of the journey we were on spiritually. In India I had come to the somewhat worrying conclusion that Buddhism was just as riddled with ridiculous dogma as was Christianity. This had been all the more reinforced by the visit to the Tibetan high plains and its temples. I had furthermore been put in a spiritual high by our walking of Tiger Leaping Gorge. What I wanted was something to help focus my feelings I had taken from that walk.

“We go to Wudang,” I said with confidence.

It was, thankfully, off season when we got there. The nearest train station was in a city at the foot of the mountain and required us to venture out and find transport to the high “resort” town that leads to the climb up the steps. Walking out of the station carrying our bags, our faces white and conspicuous, drew friendly humorous smiles from the locals. I could see what they found so full of mirth as our backpacks were large and augmented by front packs and hand baggage too. We must have looked like two turtles to the burghers of the town. However, they were more than happy to help direct us to a taxi that could take us to the bus up the mountain.

We were dropped off at a tourist gate area where we walked through a semi deserted open-air shopping arcade to a line of ticket booths. The cost of entry was quite high, but not so high we wouldn’t pay it. I guess that this is the Chinese way of preventing people from just living on the mountain without permission (it is a UNESCO Word Heritage site). It was all very official, like entering Disney World.

After the gates came a local bus. That journey was through miles of wild and woolly country of a wonderful green interspersed with the occasional martial arts temple until arriving at a mountain town built almost vertically. There we checked into a deserted hotel (I am sure that we were the only guests as the room water was not heated) and then wandered around the town looking for food for the night and the next day’s excursion up the mountain. That night we slept in its shadow and I dreamed of the ancient tales of Wudang.

The Daoist history of the mountain is long, very long. Daoism itself started as an almost shamanistic belief system before developing into the basic form centred on the belief in a great spirit of nature that is fundamentally weaved into reality. This unknowable and ineffable spirit, named “the Dao”, affects the world and by living in accordance with it great benefits can be garnered. The rest of Daoism is the discussion of the unknowable and its effects together with “research” into how to gain the benefits. This research was/is undertaken in the high mountain retreats/temples and Wudang is the home of one of the most important. There are something like 20 temples dotted along the mountain slope and it is topped with the great Purple Cloud Temple high above the cloud’s level. It was to this that we wanted to walk/climb.

Yes, I know this sounds like Star Wars. There is a reason in that Daoism was the inspiration for “the Force”.

Eventually, as with all religions that survive, a myth was built by the “vision” of a certain person. This form of Daoism suddenly had gods, including the emperor of China, and – even more strangely – rules to be followed by a priesthood. This was given the rubber stamp of the government and is the main form still found in China today.

Many things we take as fundamentally Chinese, such as the Ying Yang symbol, come from Daoism and it has affected Chinese medicine, literature, art, pottery, the fundamentals of society and what it means to have faith.

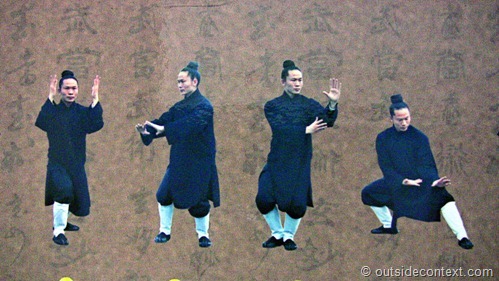

However the most commonly encountered effect (if you are western) is how it has changed the martial arts forever. The most famous tale of Wudang is that Tai Chi was invented here by ex-Buddhist monk Zhang Sanfeng. Who, while watching a snake and a crane fight one day, realised a great secret regarding the nature of power and flowing of energy. This is a secret at the heart of Wudang martial arts, which as “softer” than the more structured and rigorous “hard” styles found in the north. This split also follows along the lines of Buddhism, which had a serious schism after the 6th Zen Patriarchy was awarded to a temple kitchen-hand (the fantastic Huineng) on the basis of a single poem and leading to a sort of north south divide. Thus it follows with the martial arts of the two areas. This is – of course – painting hundreds of years of history with a broad-brush, but it is true that one of the reasons Daoism and Buddhism intertwined so much is through the “expression” of the Dao found in the martial arts.

Proof can be found in the detail behind the legendary stories. For example it is now known that the Tendon Change Classic (the famous “manual” of the Shaolin) is actually Daoist. This is obvious when one see’s the movements performed as they are clearly Qigong (literally “Life Energy Cultivation”) exercises taken out of context.

In the end, whether Sanfeng truly invented Tai Chi here or not, it is true that this mountain is the heart and birth place of a lot of important special martial traditions and principles. Wudang martial arts’ is a soft core over a hard frame. Gentle movements for using the energy of the attacker against himself. This method illuminates a fundamental truth about the movement of energy in the body (and by respects in the Universe, Daoism would claim). Meeting a blow with a defensive block – like in formal Karate styles – can lead to as much pain in the blocker as the blocked. Force on force. What they teach in the softer arts is to meet force like water, to absorb it, to grasp it in enveloping control and to then to “place” it (usually on its own head). I always council students to imagine it alike the power of the sea; flowing back then forwards, unstoppable yet yielding. Strong enough to break down cliffs and erode valleys, yet supple enough to give when it needs to.

This is core Daoist philosophy expressed through combat. For the Daoist, it is to express the Dao and be connected to it.

These principles have travelled far from this place and can actually be found in many Dojos’ of the west today. The main route of this influence follows Chan Buddhism’s journey through China and into the countries further east. The truth is that Chan left China changed into something new. It had now an element that had been left out of the Indian Buddhist form’s journey over the mountains of Tibet. The newly-adopted Daoist principles had made their mark and the two great philosophies ruled China for generations intertwining in ways as yet fully unravelled. So, when eventually Chan left China, and went to Korea and Okinawa, it had a strong undercurrent of Daoism in it.

When it got to Japan it was named Zen.

So, if Buddhism is Zen’s father, then Daoism is surely its mother. The Japanese had by this time invaded Okinawa and, legend has it, took its fighting arts back with to the homeland to become Karate. Karate came to the west (and to England through the great Vernon Bell, who I once met shortly before his death), where it remains today and each week you can see white pajamaed students in thousands of Dojo’s, regardless of their “style”, directly practice the principles first created in the philosophy of Daoism founded in Mount Wudang.

That is quite a heritage.

True, in western styles, the soft energy is often “pushed down” and minimised, but some still have it where you can see it. I studied such a style for a few years, Goju Ryu, where they have a kata (ritual movements against imaginary attackers) that is almost exactly a Wudang form practiced in a different timing.

I was eager to be able to understand the philosophy behind this flowing energy, for I had felt it many times in the martial arts and it raised many questions in my mind. Such as: How can a little master, such as my small 72 year-old master of Aikido, Don Bishop, be able to throw someone my size with no effort at all? How did sensei Humm of London Kendo be able to defeat any student half his age without being hit or wearing armour? I knew this subtle mastery of the energies came from long study, but I also knew that there was something more, something they were “tapping” into. Even if they didn’t know it. Like a man dropping into a great stream and briefly using its energy to float down river rather than walk. What was this stream? Where did it come from? And why was its use both gentle yet powerful?

I woke in the morning ready for the climb. Or at least I remember thinking I was ready. I wasn’t. At all.

One of the founding principles of Zen and Daoism is that self-improvement (leading to enlightenment) comes through effort. It often comes, however, while doing something else other than the learning part of the practice in question. You need to be doing and not learning. Focussing on the territory and not the map. Spiritual growth can be in the most simple of actions; the knuckle press-ups of Goju Ryu Karate or the gentle moving meditation of Tai Chi. It can be the daily Zen of gardening or the quiet meditation of the tea ceremony. The result is a type of mental reprogramming. Not for nothing has Zen and Daoism been compared to psychotherapy.

I was about to experience what was, for me, the greatest expression of this “practice without practice”; the walking up of the 20 thousand steps up mount Wudang. That effort, and it was an effort I quickly realised, was the point of the Purple temple being at the very top of the mountain. Not so that it is closer to heaven, but so that you must rise, and work to rise, and thereby be able to let go enough to feel the flow of the “great stream” of which I wrote. For while that stream is there, it is like the bottom of a pond, or something only seen out of the corner of your eye, you can only see it when the waters are calm, or your mind distracted.

20 thousand steps is quite a distraction.

We started by walking up and through the town until we came to a path leading a winding journey around the mountain.

This path snaked ever upwards and disappeared into the trees as its bends followed the contours of the slopes.

We had no idea where this journey would end as the path bent so much as to obscure more than the next 100 meters. It was a well built path with only a few other walkers other than locals selling their wares. Soon the town was left far behind and we were greeted with amazing views of the surrounding mountains covered in forests flowing uninterrupted right up to our feet. They were some of the most beautiful I have ever walked.

The sun was mostly absent, and this gave a parallax shaded appearance to the distance which enchanted more than detracted.

The sections of steps started lengthening after half an hour as we rose through and past grotto’s labelled as the ancient homes of hermits practicing alchemy of both the potion and martial arts kinds.

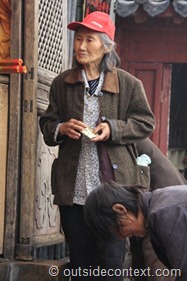

Along this forestry route we kept encountering all sorts of locals who, much like in Tiger Leaping Gorge, looked ancient and yet could hop up the steps with the grace and power of one who has been doing it all their lives. They bounded past us with no effort at all.

Next came the palanquin carriers who also didn’t appear to be struggling despite having to carry rich looking Chinese on their backs straight up the steps.

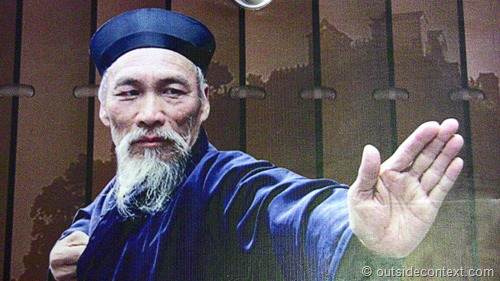

Being carried up the mountain was to fundamentally miss the point of its existence, but I guess this depends of your spiritual position. After this section we regularly came across temples that the path ran directly through. Fantastic courtyards with burning censer offerings. On the walls of the buildings we noticed photo diagrams of the martial arts of Wudang and some of the current masters. They were somewhat touristic and unrealistic, but great looking.

There has been a revolution in the martial arts in recent years, mainly brought about by the American martial forms. This revolution rejects heritage, myth and the religious foundations of most of the arts (most obvious in what is called Kung Fu) and focuses on a single question, “does it work?” This has given rise to Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) that wants to televise the answer to this question. I personally would never bemoan the MMA world, I have fought too many of them to disrespect their talent, but I am a Daoist and avid historian so the legends fascinate me. I cannot help but feel that a hidden truth, placed in the older forms, is there to be discovered. I have seen too many amazing feats by martial arts masters to deny this. Does it work? Yes, I can attest that it does. But, if the ability to rain pure destruction on your enemies is your only wish then MMA is perhaps better for you. For me, I want a way of life that illuminates, pleases and also enables me to kill should I need to. The thing is, once you have studied martial arts for long enough then combat brought about through fear no longer affects you. In other words, most masters I have known are very kind, calm and gentle people. I just strongly suggest you don’t try and mug one.

The steps now became steeper and the stretches of carved stairs longer and longer.

Together with the fact that we were half way up a mountain meant that we laboured to breath well and this journey was taking a toll even if we were really enjoying it. Indeed I remember holding hands, smiling, laughing, making jokes and having a great time.

As we passed English signs explaining some of the history of the mountain we stopped, read and discussed. The path remained very high quality and the areas were very clean. All in all, it was wonderful.

Eventually we came to a large collection of buildings. To get this far had taken over 3 hours. This area was really busy and had lots of rich looking tourists.

“Where did all these people come from?” Cesca said.

“I don’t know, but they don’t look at all tired,” I answered.

Indeed they did not, in fact they distinctly looked like the sort of people that would not toil to climb these steps. The mystery was solved when we walked around the corner and saw the massive Alpine style cable car station. Someone had built a shortcut up the mountain for the tourists entirely missing the point of its existence. But, hey they got to see the view.

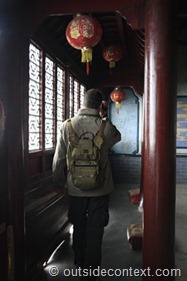

We ate lunch here and then pressed on into the temple complex itself. These buildings were in very good condition and each doorway had English explanations of the history of the forthcoming room.

Steps up between the buildings were now chain-lined and thousands of people had attached padlocks to the links. Each padlock had an inscription in Chinese.

I had seen this before and I knew that they would be a booth somewhere with a little man offering to carve the inscription for you. Eventually we made it to a temple which purported to offer good luck if you walked around the giant statue inside and we duly did although it was very cramped for someone my size and I had visions of being stuck behind this carving forever.

After this we ascended to the peak above the roofs. This was another hike up multiple stairs, but we were excited by this point.

As we came up to the very peak we were now within the cloud layer. In summer this would probably be above it and a surreal experience, but for us it was like walking into the clouds.

Atop the peak is a courtyard of around 100 meters a side and in the middle was a large grotto style temple building carved from brass and lined with pillars.

It was quite a sight and outside stood a very old looking priest with a huge classic Chinese beard. He looked a little swamped in tourists, but also very used to the experience.

If the cable car wasn’t available, I have no doubt we would have been the only ones on this peak. Eventually we walked down the rear of the courtyard and through a winding stair until we were back in the main temple area.

With unspoken agreement we started back down the steps.

Going down was harder. My legs burned something chronic at having to stretch to step down and I could tell we would be suffering in the coming days. As we passed people we gave out words of encouragement to those climbing up who looked like they couldn’t tell how long the rest of the journey was.

After only 2 hours we were back in the base town and we walked to the hotel.

They wouldn’t let us check in. The hotel was closed it seemed. OK then would they let us have a shower? No. I must admit Cesca and I got very upset at the cultural stubbornness these people displayed. The fact we could not speak each other’s language exacerbated it and eventually it resulted in both parties getting seriously pissed off. So, wet through from the climb we lugged all our gear off the mountain and back to the city where we found a hotel and fell into bed.

Sure enough the next day my legs were in extreme pain and walking around the city finding food was a slow tiring business. We found a burger bar and tucked into chicken burgers.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but I was not the same person who had climbed that mountain. Something had changed. It wasn’t to crystallise into a public exaltation of that change for nearly a year, but nevertheless it started here. I had read so much, studied so much and listened to so many voices on my journey to a spiritual awakening that it was as if those last 20 thousand steps and the Wudang peak truly capped it off.

I had finally seen the “whitespace” that framed the world, the negative image that gives form to all the positive images we see around us. I had found the core of this feeling I had been carrying around for 30 years and my journey from the child first encountering a Zen Buddhism book in a little bookshop in Maldon was now almost complete.

A lifetime of asking, questioning and study. At the Christian churches of my childhood, at the dinner tables of my mother and father, in the GCSE English class of my teachers, in the A-Level Philosophy of Plato, in the degree Philosophy of Nietzsche, in my 20 years of martial arts study, in my discovery of Buddhism, my walks listening to the Zen master Alan Watts, my year long journey to the East around the temples of Asia, China and India and now finally in our ascent to the top of this mountain bringing it all together and showing me the connecting structure in one place.

In a type of Satori and with it a peace.

I believe there is an energetic and currently unknowable flowing “spirit” to the universe that is the core of it being in existence. It isn’t a God who loves us like a father; it is bigger than us and our petty dogmas. It is the Starmaker; an operation of reality that we are barely aware of and it means that I believe there is no duality in the universe. Living with it is to live fully. It is like the music of the universe playing all around you and one simply has to hear it, accept it and let its celestial dance guide you through the moments of your life to find peace.

Truly then I believe that we do not see reality like it actually is. There is something more, but it is not away from us in a heaven, it is right here all around us and we are a part of it, woven into its fabric, in the same way that the valley is a part of the mountain.

The mountain that showed this to me was Mount Wudang, Hublei province, China.

Years later I had a conversation with some incredulous Christian friends that went like this:

“The way you talk, Basho, you are on the path to Christianity,” he said and they smiled to each other, “at the moment you are simply denying God, you must listen to him”.

I smiled back, “No my friends,” I said, “I am not denying God. I have climbed the mountain and opened the door at the top. I just didn’t find Jesus on the other side, I found the Universe and with that came spiritual peace.”

Regards,

Basho

Thanks for reading this article – I hope that you liked it. If it has left you wondering, “Just what is this Daoism stuff?” Then the answer – of sorts – can be found here: What is Daoism?